September 27, 2019

At Joyce Farms we pride ourselves in paying attention to the little things. Even the REALLY little things, like microbes in the soil. The world beneath the soil surface is full of life and incredibly complex, far more so than life above the soil surface. Without their action in the soil, we suffer. When they are present in large numbers and highly active, we benefit.

A single spoonful of healthy soil contains more life than there are humans on Earth.

When it comes to healthy soil, healthy plants, healthy animals and healthy people, the little things do matter --- a lot. That is why our focus on producing flavorful and nutrient-dense food starts with the soil, and not just the soil itself, but those tiny microbes residing in it.

The soil’s population of microbes is diverse, made up of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and nematodes, and others. For now, we want to focus on one -- mycorrhizal fungi.

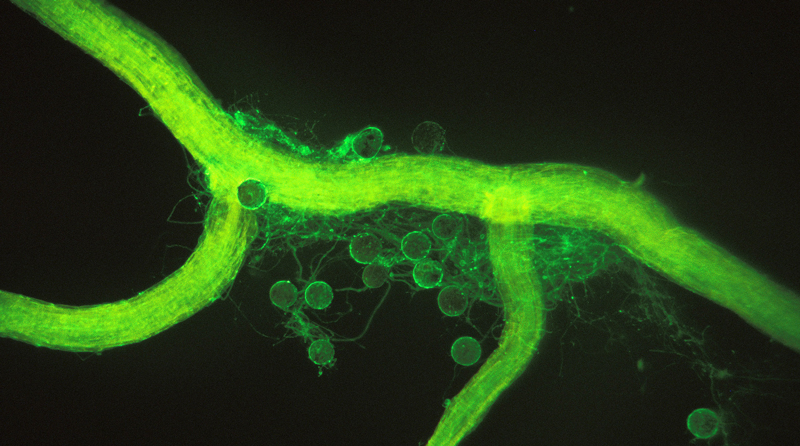

Mycorrhizal fungi are microscopic thread-like organisms that play an incredibly important role in healthy soil, and therefore, in the production of truly healthy, nutritious food. We are now discovering how critical that role is, and what happens when they are not present in the soil in large numbers.

The activities of mycorrhizal fungi beneath the soil surface are just as sophisticated and purposeful as anything we can point to above ground.

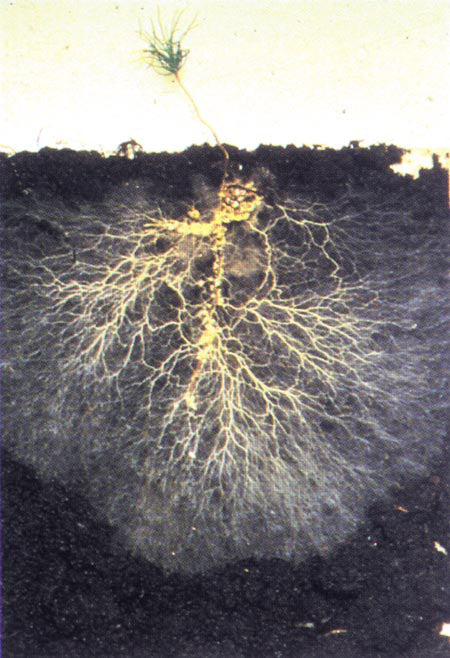

Mycorrhizal fungi can create an incredibly powerful, interconnected exchange network between plants... much like the world wide web of soil. When given the chance, and not disturbed by degenerative farming practices, mycorrhizal fungi spread their feathery tendrils throughout entire fields, attaching to plant roots, connecting every plant in a web of constant communication and mutually beneficial trades.

Plants need nutrients from the soil, but most of those nutrients are 1) out of reach of the plant roots, and 2) bound in the soil and must be dissolved before the plants can absorb them. Mycorrhizal fungi can help. They can greatly extend the reach of the plant roots, and also produce powerful enzymes that break down nutrients and transfer them to the plant… but only for a price.

The mycorrhizal fungi want to eat too, and they prefer the sugars and fats that plants exude from their roots. So, in exchange for nutrients, mycorrhizae receive plant root exudates that are loaded with carbon (produced from CO2 pulled from the atmosphere during photosynthesis).

Mycorrhizal fungi and plants are able to make sophisticated, spur of the moment decisions about their trades, always negotiating the best “deal” they can. It is the world’s oldest bartering system.

In this delicate dance between plants and mycorrhizal fungi, plants can reward high performing fungi with more sugars and punish poor-performing fungi with less sugars. Fungi can also give more nutrients to plants that “feed” them more sugars.

Mycorrhizal fungi can "feed" more nutrients to a plant when it is “paying” them well, or they can store or "hoard" nutrients and wait for a better offer (either from that plant or other plants) before they release the nutrients.

For example, in one experiment, carrot roots and fungi were grown together in a petri dish divided into three equal compartments. Interestingly, in one compartment the carrot roots provided the fungi with more sugars than in the other compartments. The carrot that was willing to trade more sugar with the fungi received more nutrients in return.

These fungi can also move nutrients back and forth from “rich” regions in the rhizosphere to “poor” regions. In the poor regions, where nutrients are scarce, the plants are willing to pay more carbon-rich sugars to get them from the mycorrhizal fungi. Through this feedback system, soils that are lacking nutrients can quickly increase their nutrient availability through this mycorrhizal pathway. Nutrients flow both ways, too. Research shows nutrients oscillate back and forth through the mycorrhizal network every five minutes at precise timing.

As mycorrhizal fungi are forming their network, they use a sticky biotic glue called glomalin to attach to plant roots. Not only does this connect plants together over the fungal “exchange network,” it also binds tiny soil particles together into larger clumps of soil called aggregates.

When the soil is aggregated, it allows for increased oxygen and water infiltration. Without aggregates, rain pools on the soil surface, then runs off, eroding the soil and carrying tremendous amounts of topsoil, nitrates, phosphates, and harmful agricultural chemicals with it.

Mycorrhizal fungi also protect plants from drought by storing an “emergency fund” of water, for not-so-rainy days. Since mycorrhizal fungi can actually penetrate plant roots, they are able to directly place water molecules inside the plant roots for use in periods of dry and drought conditions.

However, like many other functions performed by mycorrhizal fungi, there is a selfish motive involved. They want to be fed during periods of drought, too. So, by placing the water molecules inside plant roots, they assure themselves that the plants have adequate survival to continue to supply them with steady meals of carbon-rich root exudates.

Different plant species produce varying arrays of what are called plant secondary and tertiary nutrient compounds, which are medicinal in nature and promote disease resistance and pest resistance in other plants. They also provide medicinal benefits to animals and humans.

These compounds are transferred from plant to plant via the mycorrhizal highway. Without this occurring, plants are far more susceptible to fungal diseases and to pest insects. In fact, mycorrhizal fungi are the principal immune system for plants against fungal root diseases.

In the past several decades, the use of fungicides by farmers has increased significantly, because typical agricultural practices (like tillage) destroy mycorrhizal fungi populations. In addition, the fungicides used to combat plant fungal diseases are not organism-specific, so they kill not only the target disease-causing organisms, but also the mycorrhizal fungi. This leads to continued disease, and continued use of fungicides, which becomes a vicious cycle.

That is why we practice Regenerative Agriculture at Joyce Farms.

By eliminating tillage, we stop the destruction of the mycorrhizal fungi. By implementing practices such as diverse cover crops instead of perpetual monocultures, and adaptive livestock grazing that stimulates mycorrhizal populations, we not only reduce, but eliminate the need for fungicides. We escape the vicious cycle and turn things back over to Mother Nature.

Soil microbes truly are the foundation of all health, both below the soil surface and above. More than 80% of all plants existing in the world today have developed relationships with fungi. Still others have relationships with bacteria in the soil. If we were to purge the soil of microbes, we would also purge the soil of plants, and purge our world of the ability to produce food.

Implementing agricultural practices that damage or destroy these soil microbes is only doing harm to ourselves and all life around us. Conversely, implementing true regenerative practices that foster, facilitate, encourage, and stimulate these soil microbes provides immense benefits -- our soil is healthy, our crops are healthy, our livestock are healthy, we are healthy, our ecosystems are healthy, and our climate is healthy.

These tiniest of creatures hold the key to solving the primary issues we face today that seem so daunting. If we simply provide for them, they will provide for us. That is why regenerative agriculture and soil health is so important to us at Joyce Farms, and why it should be important to you, too!

January 14, 2026 2 Comments

Joyce Farms is introducing Signature Angus Heritage Beef, a pasture-raised, single-farm Red Angus program designed to carry our heritage beef story forward and serve more customers over time. Heritage Aberdeen Angus Beef will remain available in limited quantities until early 2026 as existing inventory is sold.