June 16, 2020 0 Comments

In our last blog post, we discussed the tremendous array of phytonutrients available from plants and pasture-raised proteins.

Diversity, particularly plant species diversity, is crucial in building a wide range of health-boosting and healing phytochemicals.

Farm landscapes that encourage and build diverse arrays of plants become plant, animal, and human nutrition centers and pharmacies. And, unlike a typical pharmacy, you don't have to worry about drug interactions, side effects, or overdosing. The medicines we obtain through our foods are in perfect balance and readily available for health and healing.

As farmers, we focus on fostering landscapes that provide a variety of foods for the herbivores, omnivores, and carnivores beneath and above the soil surface.

These landscapes are in sharp contrast to farm landscapes where monoculture crops and livestock production are the norm.

Animal health greatly improves when they can forage from a diverse array of plants. They stay healthy, require no antibiotics, and grow more efficiently with less carbon, nitrous oxide and methane emissions.

Livestock grazing in diverse environments actually are healthy for the climate rather than harmful.

It is only when they are grazed poorly, in monoculture pastures, or in feedlots on grain rations, that we have problems with harmful greenhouse gas emissions from our livestock.

This makes complete sense from a historical ecological perspective, as there were once hundreds of millions of wild ruminants roaming the grasslands, prairies, savannas, and woodlands of the world. If grazing animals were harmful, then nature was conspiring against herself for tens of thousands of years!

At Joyce Farms, we strive to provide as diverse a plant environment to our livestock as possible. As a matter of fact, this diversity is increasing each year.

Herbivores will often eat from 50 to 70 plants a day, if provided a phytochemically rich mix of grasses, forbs, shrubs, and trees.

These animals eat a variety of foods for several reasons:

These are the same reasons we should eat a variety of foods daily.

It is the secondary nutritive compounds that are our personal pharmacy and nutrition center. Plants grown in diverse communities have enhanced above ground (shoot) and below ground (root) phytochemicals. This gives a phytochemical richness to the plants we eat, the meat we eat, eggs and dairy we eat. If grown in a diverse plant environment.

Amazingly, this phytochemical richness provides a host of benefits to the plants themselves, including:

Yes, plants can protect themselves against animals overgrazing any individual plant in a plant diverse environment. However, monoculture and low diversity environments encourage animals, including wild ruminants, to overgraze. These types of environments make plants and animals more susceptible to environmental hardships.

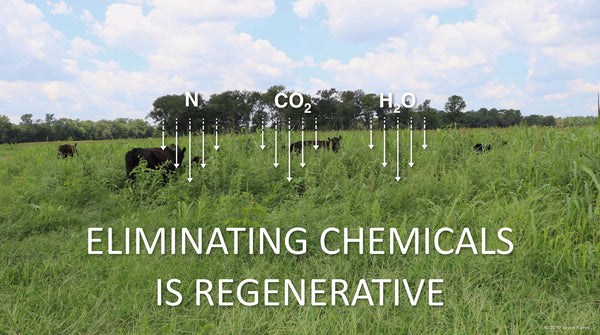

In most of modern agriculture, the production and array of these vital plant phytochemicals (secondary compounds) has been reduced. Monoculture systems have replaced natural phytochemical defenses with synthetic fertilizers, herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides. Livestock operations have replaced nature’s pharmacy with antibiotics and anthelmintics (anti-parasitic drugs) to treat disease and parasites. There are even attempts to genetically engineer back into plants the resistance to disease and pests they once had.

We must remember that plants and herbivores have been playing these games for a very long time. They had established a balance that worked well. Modern agriculture interrupted that balance.

We need to understand that plants are sentient beings, receiving and responding to sensations. They are not organisms that feel nothing or understand nothing. Plants can “see” different wavelengths of light, “breathe” through the stomata on the surface area of their leaves and stems, smell, taste, talk and listen in biochemical languages, detect through their smell and taste chemical compounds in the air and on their tissues.

Plants “hear” the sounds of pest insects, such as caterpillars eating on a neighboring plant and respond in self-defense by producing volatile compounds that alert other plants in the community to the predator. These volatile compounds can be sensed by beneficial insects and birds that prey on the pest insect. The volatile compounds also attract pollinators, birds and animals to perform pollination services and seed dispersal.

Underneath the soil surface, the biological world is busy performing vital functions as well. Plant roots interact with soil fungi and bacteria as these microbes search for water and nutrients. The plants transfer food to the soil microbes through sugars spewed out from their roots (exudates). The bacteria and fungi capture nutrients in the soil and feed the plant host. The secondary compounds from the plant root exudates can attract, deter, or even kill insect herbivores, nematodes, and microbes. These same exudates can also prevent competing plants from establishing themselves.

Nature plays a complex offense and defense that has been honed by the interaction between soil microbes, plants, insects, and animals for eons.

This game plan works and works very well. It provides the pharmacy and nutrition center for all these organisms, and for us.

If we attempt to work against nature, we interrupt this delicate balance, and we disrupt the vast array of medicinal and nutritive compounds needed for optimum health.

Modern agricultural devices are foolish compared to nature’s devices. That is why we must always strive to work with nature, and never against. Nature always wins!

Written By Dr. Allen Williams, Ph.D.

Written By Dr. Allen Williams, Ph.D.

A champion of the grass-fed beef industry and the growing Regenerative Agriculture movement, Allen helps restore soil health, increase land productivity, enhance biodiversity, and produce healthier food. He also serves as Joyce Farms' CRO (Chief Ranching Officer). Learn more about Allen

June 09, 2020 0 Comments

Did you know that the health of plants, animals, ecosystems and humans is inextricably tied to plant phytochemical diversity?

Phytochemicals are compounds naturally produced by plants that help the plants thrive in challenging conditions, fight off competitors, pest insects, and disease.

When you bite into a juicy strawberry or blueberry, enjoy vibrant green lettuce or spinach, munch on a tomato, or chow down on a juicy steak or hamburger you consume much more than vitamins, minerals, protein and fiber. You also benefit from the incredible richness of phytochemicals.

Phytochemicals are comprised of four main categories:

All big words, and they have BIG impacts on our health.

All of these phytonutrients contain powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that are crucial to our health and well-being, and our eventual longevity.

There are tens of thousands of these phytonutrients found in plants, and in the meat of animals that eat those plants.

Why do we all eat, and yet we still have significant health problems in the U.S.?

It is because not all foods are created equal.

Not all tomatoes are the same, not all chicken is the same, not all beef is the same, not all pork is the same.

The soil those plants grow in, the plants that are growing there, and the plants that the animals eat all determine the degree of phytonutrient richness in the foods we eat.

The problem with modern agriculture is its industrialized approach to food production -- planting monoculture and near monoculture crops and pastures, degrading our soils, and destroying soil biology.

Plants thrive when grown in diversity, with many plant species all growing within close proximity of each other, able to share nutrients and phytochemicals through the vast underground network of mycorrhizal fungi.

Modern industrial practices like tillage and use of chemicals, synthetic fertilizers, fungicides, and insecticides can greatly reduce plant phytochemical production and richness.

This shift away from phytochemically rich plant and animal foods to the highly processed foods so many eat today has enabled more than 2.1 billion people to become overweight and obese.

This, in turn, has led to higher incidence of diet-related disease in humans, like diabetes, heart disease, autoimmune disorders, and even various types of cancer.

Evidence supports the hypothesis that phytochemical richness of herbivore diets significantly enhances the phytochemical and biochemical richness of the animal proteins that we eat.

Animal proteins from animals eating phytochemically rich diets do not lead to heart disease and cancer. Instead, they actually provide protection against those same diseases, just like the phytochemically rich plants do.

It is only when these same animals are fed high-grain rations and monoculture pastures that their protein becomes an issue for our health.

That methane issue we hear so much about with ruminant livestock? Plant phytochemical diversity stimulates microbes in the soil, such as methanotrophs, that digest that methane. This is how nature took care of methane from the hundreds of millions of wild ruminants that once roamed the face of the earth.

At Joyce Farms, we implement regenerative practices that create phytochemical diversity in our pastures. We restore our soils to their historical ecological context. We sequester carbon and return it to the soil so it can nourish the soil microbes vital to providing our plants and livestock with nutrients.

We recognize that our food is our medicine. We invite you to share in our phytochemically rich foods and enjoy truly healthy meals.

Written By Dr. Allen Williams, Ph.D.

Written By Dr. Allen Williams, Ph.D.

A champion of the grass-fed beef industry and the growing Regenerative Agriculture movement, Allen helps restore soil health, increase land productivity, enhance biodiversity, and produce healthier food. He also serves as Joyce Farms' CRO (Chief Ranching Officer). Learn more about Allen

April 22, 2020 0 Comments

Human behavior has tremendously impacted the state of our planet for thousands and thousands of years. In fact, if we traveled back in time, even by a few centuries, we may not even recognize the landscape of our own local regions and communities.

On Earth Day, we want to celebrate the incredible essential resources that Mother Earth provides, and to learn from the mistakes of our ancestors by recognizing the (often unintended) consequences they have had on our ecosystems. The practices we use today, in agriculture and beyond, will shape the future of our planet and all who inhabit it.

Most of us have a very narrow vision of what our region was like before our lifetimes. We think only in terms of what we have experienced, or what our grandparents told us.

The truth is all of us have experienced an already significantly degraded ecosystem. In most regions of the U.S., our soils and landscape has been seriously degraded for 300 or more years.

European settlers started the eastern U.S. degradation process in earnest by the early 1600s, in the Atlantic states. Before that time, the American landscape looked much different.

There were hundreds of plant species growing throughout the southern U.S. prairies. The eastern U.S. was filled with bison, elk, deer, and even antelope.

These wild ruminants kept the prairies a prairie and the savannas open and clean of dense, thick understory. They had a profound impact on the landscape of the southern U.S. and all of North America, and Native American tribes depended on these animals for sustenance, and famously used every part.

However, by the mid- to late-1700’s most of the bison, elk, and antelope were eradicated in this region due to the degenerative farming practices that early settlers brought with them to America.

Single tree plows pulled by oxen, mules, or horses did a great job of turning under the prairie and wooded savanna soils of the east, which started the erosion and degradation process. They planted monocultures using the agricultural knowledge they brought with them from Europe and the British Isles.

They were so good at destroying the soil that in 1796, George Washington stated:

“A few years more of increased sterility will drive the inhabitants of the Atlantic states westward for support; whereas if they were taught how to improve the old soils, instead of going in pursuit of the new and productive soil, they would make these acres, which now scarcely yield them anything, turn out beneficial to themselves.”

Think about the gravity of that statement! A brand new country was already suffering from the wounds of poor agricultural practices.

In under 200 years, our ancestors had destroyed the soil health of the Atlantic states, and they did it without the aid of the massive diesel-powered equipment we have at our disposal today.

Planters in the southern Atlantic states had so worn out those soils that, by the early 1800s (as Washington had predicted), they started looking westward for new lands and virgin soils.

Wagon trains of settlers headed west to the prairies and savannas of what is now Alabama and eastern Mississippi.

By the time of the Lewis & Clark expedition from May 1804 through September 1806, things had changed so drastically in the eastern portion of the U.S., that what they encountered and viewed as they moved westward in the early days of their journey was a distinct anomaly to them.

On July 4, 1804, William Clark wrote these words in his diary:

“The Plains of this countrey are covered with a Leek Green Grass, well calculated for the sweetest and most norushing hay --- interspersed with cops (copses) of trees, Spreding their lofty branchs over pools, Springs or Brooks of fine water. Groops of Shrubs covered with the most delicious froot is to be seen in every direction, and nature appears to have exerted herself to butify the senery by the variety of flours (flowers) raiseing delicately and highly flavored above the Grass, which strikes & profumes the sensation and muses the mind, …. So magnificent a senery in a country situated far from the Sivilised world to be enjoyed by nothing but the buffalo, elk, deer & bear in which it abounds……”

Now, Clark was not much on correct spelling, but he did write beautifully. This statement was written from a bluff overlooking the Missouri River near present day Doniphan County, KS.

What strikes me about Clark’s observations is that this sight was so astounding to him. It was so unusual that he wrote about it as if he were viewing the Garden of Eden.

His experience growing up in the eastern U.S., born in 1770 in Virginia, was of a country already devoid of the bounty he witnessed in the far northeastern corner of present-day Kansas in 1804. He had never seen such an amazing sight and it obviously stirred his very soul.

Fast forward just another 100 years and that same midwestern prairie that Clark wrote about was well on its way to becoming a part of the 1930s Dust Bowl.

We often hear today that cattle, and other grazing animals, compact the soil and many farmers want no part of cattle on their farmland. However, when the early settlers first put the plow to the prairie soils (which had been trampled and roamed for centuries by bison and other ruminants), they found them easy to turn over with a plow pulled by a mule. So easy that these early prairie farmers created the disaster we know as the Dust Bowl. These same midwestern soils today would barely be scratched on the surface with a single tree plow.

So, if grazing livestock compact soils, then just how did these early settlers so easily plow the prairie soils? In fact, poor grazing practices do compact the soil BUT good grazing practices, such as adaptive grazing, do just the opposite - creating loose, pliable, highly aggregated soils that are easy to plant with a No Till drill.

So, what should our planet, soils, and ecosystems look like today? Just look to the past and you will open a window into our future potential with solid regenerative agricultural practices. Wherever we implement these principles and practices we see life returning in abundance. Perhaps we too can one day view a scene similar to what William Clark experienced approximately 200 years ago.

Written By Dr. Allen Williams, Ph.D.

Written By Dr. Allen Williams, Ph.D.

A champion of the grass-fed beef industry and the growing Regenerative Agriculture movement, Allen helps restore soil health, increase land productivity, enhance biodiversity, and produce healthier food. He also serves as Joyce Farms' CRO (Chief Ranching Officer). Learn more about Allen

April 02, 2020 0 Comments

By Dr. Allen R Williams, Ph.D.

As I described in yesterday’s blog, it is getting crazy out there and the panic buying is not subsiding. What is occurring in our nation, and around the world, only serves to substantiate why we need regenerative agriculture now more than ever. It is no longer just about the climate, our water quality, and our ecosystems. They are all still vitally important, but an even more pressing need has emerged.

In the past several decades our agriculture and food systems have become increasingly consolidated and centralized. For example:

Why is this a problem when faced with a pandemic such as the coronavirus? Look no further than your bare local grocery store shelves. Food has to travel more than 1500 miles in the U.S. to get to its final destination of a grocery store or restaurant.

As I explained in my prior blog, we do not have a shortage of food in the U.S., as we have more than 8 billion pounds in frozen stocks. What we have is a transportation problem that is easily overwhelmed.

Centralized food production, processing, and cold storage seem wonderful and awfully efficient when everything is working well. However, when things break down, we find ourselves scrambling for food.

In addition, the larger the farm and the larger the processor, the more people there are that touch your food and everything it comes in contact with. This puts us all at a heightened risk. It's hard not to be in close proximity to your fellow workers in a large, industrial scale food processing plant.

Moving back to regenerative agriculture means we can trend back towards smaller family owned farms that are profitable and support the families that operate them.

This means fewer hands touch the food being produced on those farms. And, more family farms means more local and regional processing. These plants, like Joyce Farms' plant in North Carolina, are substantially smaller than the massive plants operated by the large food companies. That equals fewer hands touching the food in those plants.

Now to be fair, the hands that touch food in any plant, large or small, are gloved hands. But, it is not just hands that transmit viruses - it is the breath of any carrier as well. I am not saying that the big food companies are bad and large plants are bad. No. They have their place. What I am saying is that if they are our only option, we limit ourselves in a number of ways.

Locally and regionally produced food allows for far more options for the consumer. It is easier to transport and get to consumers in a local market. Local and regional production supports rural economies and returns financial stability to the families that live in these rural communities.

More farms practicing regenerative principles equals healthier soil. Healthier soil equals more nutrient dense foods. More nutrient dense foods equals better human health. Better human health equals stronger immune systems and greater ability to fight off challenges like the coronavirus. Better human health is a direct result of supporting a thriving and diverse gut microbiome. That can only come from better foods.

In my next blog I will explain how the gut microbiome is the key to our immune system strength and ultimate health.

Written By Dr. Allen Williams, Ph.D.

Written By Dr. Allen Williams, Ph.D.

A champion of the grass-fed beef industry and the growing Regenerative Agriculture movement, Allen helps restore soil health, increase land productivity, enhance biodiversity, and produce healthier food. He also serves as Joyce Farms' CRO (Chief Ranching Officer). Learn more about Allen

January 02, 2020 0 Comments

Choosing a New Year's resolution can be challenging, and many of us tend to repeat the same ones each year, hoping for the best. In fact, research indicates roughly 60% of us commit to resolutions, but only about 8% stick to our goals after the ball drops.

Many of the tried and true resolutions we choose are to better our own lives, and without much repercussion, if we fall back to our old ways. This year, we ask that you consider a different kind of resolution, one that will not only improve your own life, but that can impact the future for entire generations.

As we close 2019, food production and environmental well-being have never been more threatened. Centuries of industrial agricultural practices have left us on the brink of environmental disaster, with eroded and unhealthy farmland, contaminated water sources, increasingly severe weather events from an unbalanced ecosystem, and significantly lower food quality. In our attempts to fight these problems, we ended up with more chemical use, more bare and tilled soil left exposed to the elements, and unhealthy modern animal breeds raised to grow extremely fast in confined and inhumane environments.

If industrial, and even sustainable farming practices continue, the United Nations estimates that we would only have about 60 years of farmable topsoil left. With 95% of our food coming from topsoil, it’s clear that change is needed, and that change is regenerative agriculture.

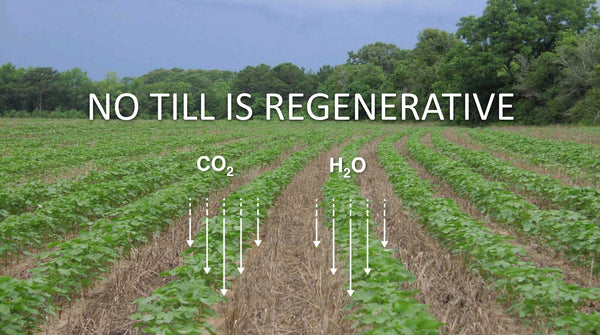

Regenerative Agriculture is a farming method that applies sound ecological principles and biomimicry to regenerate living and life-giving soil. Regenerative agriculture relies on nature, not harsh chemicals or disruptive practices like tilling.

If we restore the health of our soil ecosystem, we restore our own health, the health of our farms, our communities, and our planet. When a farmer is practicing true regenerative agriculture, we like to say, “You know it when you see it.”

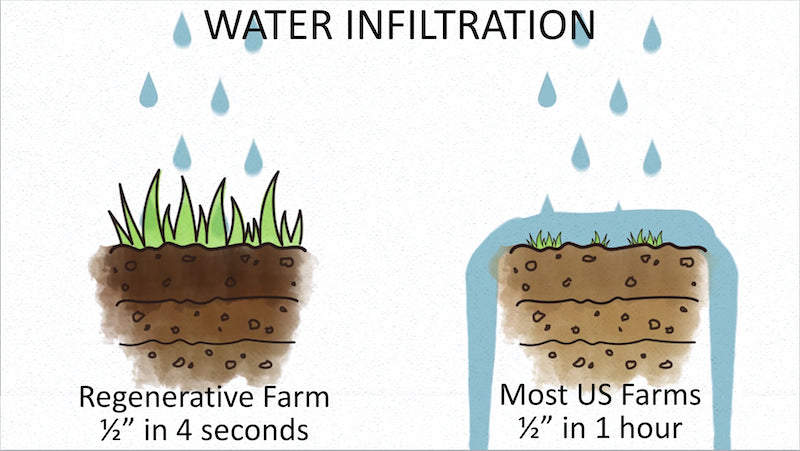

What do we see? The return of beneficial insects and pollinators, like bees, dragonflies, grasshoppers, and butterflies. The return of birds such as ground-nesting birds, song birds, migratory birds, and waterfowl. The return of wildlife such as deer, raptors, turkey, and many other furry creatures. The return of soil that actually infiltrates water and restores and recharges our underground aquifers, natural springs, and waterways. The return of a diverse plant species population.

Regenerative agriculture offers a multitude of benefits for our farms, our environments, and our food, including (but not limited to):

So, in 2020, make a resolution to support the Regenerative Agriculture movement.

Here are four simple ways you can do that:

One thing you can do to pursue your resolution is to learn more about regenerative agriculture, the basic principles and terms, and how it differs from industrial and sustainable methods. By arming yourself with knowledge, you will be in a much better position to support regenerative farming in other ways.

Here are several resources to start with:

Maybe it’s unrealistic to say you will only eat or serve regeneratively raised products. Depending on your resources, it could be done, but why not start with something more achievable?

Challenge yourself to use regeneratively raised products a couple of times a week. Chances are, once you start, you won’t want to go back to industrially or even sustainably raised products that lack natural flavor and nutrients.

If you’re a chef, start by adding a couple of regenerative products to your menu, or as a special feature. Make sure you let your customers know what makes it so special!

Once you’ve made the choice to support regenerative, the question becomes, how do I find regenerative products?

Our advice is not to rely on claims, but to engage with farmers and producers directly. Regenerative farming is a complex system, and there’s no “set and repeat” formula that is right for all farms, so it’s important to get to know the farms that produce the food you purchase. Find out what they mean when they say regenerative. Are they just composting on overgrazed land, or have they embraced all of the principles, like livestock integration, and adaptive multi-paddock grazing? Ask about their regenerative practices, or to see them in action if possible. Most farms and organizations that are truly embracing regenerative agriculture will be eager to share with you and welcome you to their farm(s)!

You may be thinking… if regenerative agriculture is as good as we say it is, why isn’t everyone using it? One of the biggest reasons is because people don’t know about it. A second major reason for farmers not transitioning to regenerative agriculture is simply fear. Fear of peer pressure from neighbors, friends, family, and suppliers if they decide to farm differently. Fear of the mountain of debt most farmers carry. Fear of doing something very different than what they have traditionally done. This fear is real and prevents farmers from doing what they should.

Regenerative agriculture is just beginning to seep into the mainstream conversation. The more educated advocates are out there, the faster we can make progress.

Talk about regenerative agriculture with your friends, your family (it makes a great holiday table topic!), the restaurants you frequent, and your social media connections. If you’re a chef using regenerative products, brag about it on your menu! It’s our responsibility to keep the dialogue going about regenerative, what it can do for all of us, and offer support to those farmers moving to regenerative or seeking a transition.

As part of our efforts at Joyce Farms, we introduced educational farm tour events and presentations to help grow awareness, but it could be as simple as a conversation or reposting content on social media!

If you don’t have experience farming or working with soil, now is a great time to start! Take up gardening in your own yard or community garden, or, look into opportunities to volunteer at a local farm. Getting some first-hand experience with the land will give you more context and understanding as you learn about soil health and other regenerative concepts.

Happy New Year from all of us at Joyce Farms!

September 27, 2019 0 Comments

At Joyce Farms we pride ourselves in paying attention to the little things. Even the REALLY little things, like microbes in the soil. The world beneath the soil surface is full of life and incredibly complex, far more so than life above the soil surface. Without their action in the soil, we suffer. When they are present in large numbers and highly active, we benefit.

A single spoonful of healthy soil contains more life than there are humans on Earth.

When it comes to healthy soil, healthy plants, healthy animals and healthy people, the little things do matter --- a lot. That is why our focus on producing flavorful and nutrient-dense food starts with the soil, and not just the soil itself, but those tiny microbes residing in it.

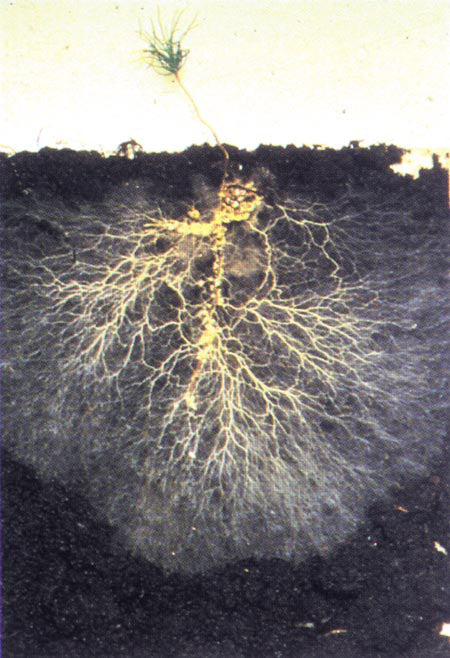

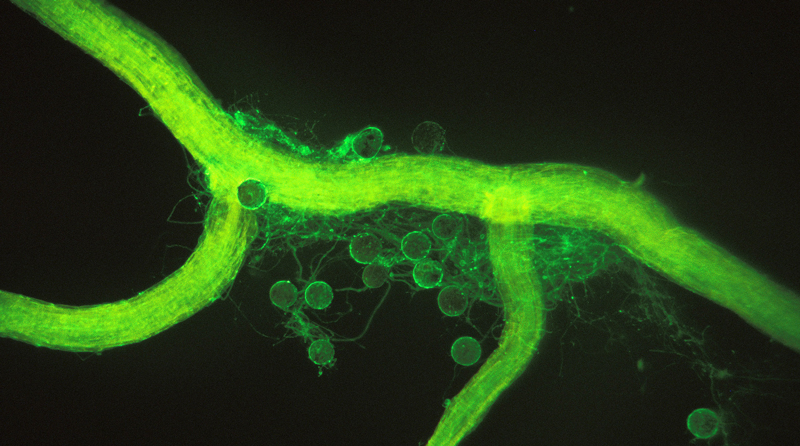

The soil’s population of microbes is diverse, made up of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and nematodes, and others. For now, we want to focus on one -- mycorrhizal fungi.

Mycorrhizal fungi are microscopic thread-like organisms that play an incredibly important role in healthy soil, and therefore, in the production of truly healthy, nutritious food. We are now discovering how critical that role is, and what happens when they are not present in the soil in large numbers.

The activities of mycorrhizal fungi beneath the soil surface are just as sophisticated and purposeful as anything we can point to above ground.

Mycorrhizal fungi can create an incredibly powerful, interconnected exchange network between plants... much like the world wide web of soil. When given the chance, and not disturbed by degenerative farming practices, mycorrhizal fungi spread their feathery tendrils throughout entire fields, attaching to plant roots, connecting every plant in a web of constant communication and mutually beneficial trades.

Plants need nutrients from the soil, but most of those nutrients are 1) out of reach of the plant roots, and 2) bound in the soil and must be dissolved before the plants can absorb them. Mycorrhizal fungi can help. They can greatly extend the reach of the plant roots, and also produce powerful enzymes that break down nutrients and transfer them to the plant… but only for a price.

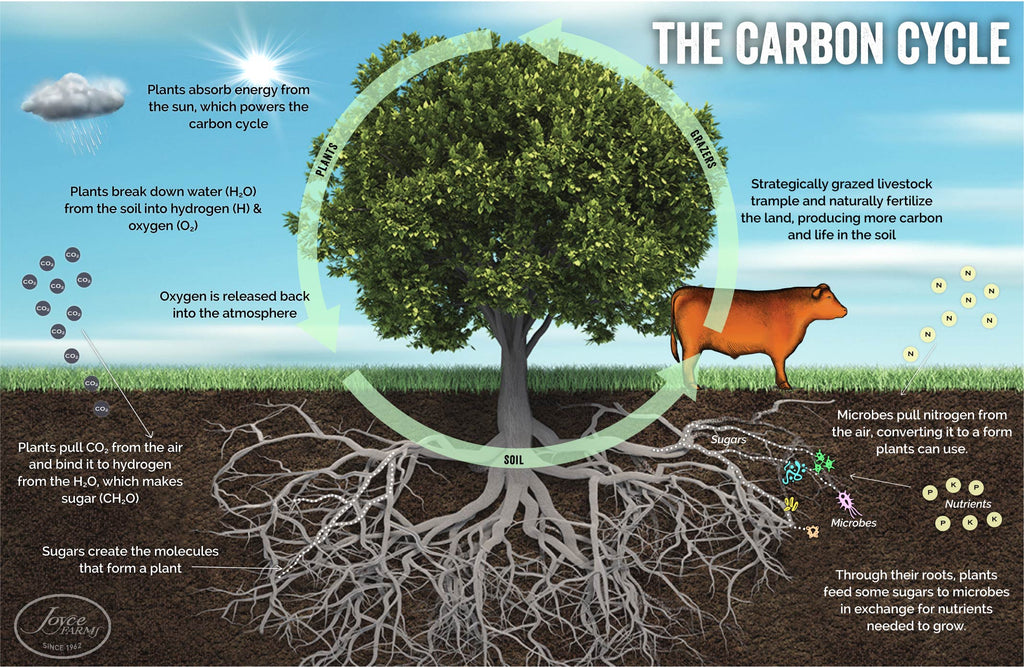

The mycorrhizal fungi want to eat too, and they prefer the sugars and fats that plants exude from their roots. So, in exchange for nutrients, mycorrhizae receive plant root exudates that are loaded with carbon (produced from CO2 pulled from the atmosphere during photosynthesis).

Mycorrhizal fungi and plants are able to make sophisticated, spur of the moment decisions about their trades, always negotiating the best “deal” they can. It is the world’s oldest bartering system.

In this delicate dance between plants and mycorrhizal fungi, plants can reward high performing fungi with more sugars and punish poor-performing fungi with less sugars. Fungi can also give more nutrients to plants that “feed” them more sugars.

Mycorrhizal fungi can "feed" more nutrients to a plant when it is “paying” them well, or they can store or "hoard" nutrients and wait for a better offer (either from that plant or other plants) before they release the nutrients.

For example, in one experiment, carrot roots and fungi were grown together in a petri dish divided into three equal compartments. Interestingly, in one compartment the carrot roots provided the fungi with more sugars than in the other compartments. The carrot that was willing to trade more sugar with the fungi received more nutrients in return.

These fungi can also move nutrients back and forth from “rich” regions in the rhizosphere to “poor” regions. In the poor regions, where nutrients are scarce, the plants are willing to pay more carbon-rich sugars to get them from the mycorrhizal fungi. Through this feedback system, soils that are lacking nutrients can quickly increase their nutrient availability through this mycorrhizal pathway. Nutrients flow both ways, too. Research shows nutrients oscillate back and forth through the mycorrhizal network every five minutes at precise timing.

As mycorrhizal fungi are forming their network, they use a sticky biotic glue called glomalin to attach to plant roots. Not only does this connect plants together over the fungal “exchange network,” it also binds tiny soil particles together into larger clumps of soil called aggregates.

When the soil is aggregated, it allows for increased oxygen and water infiltration. Without aggregates, rain pools on the soil surface, then runs off, eroding the soil and carrying tremendous amounts of topsoil, nitrates, phosphates, and harmful agricultural chemicals with it.

Mycorrhizal fungi also protect plants from drought by storing an “emergency fund” of water, for not-so-rainy days. Since mycorrhizal fungi can actually penetrate plant roots, they are able to directly place water molecules inside the plant roots for use in periods of dry and drought conditions.

However, like many other functions performed by mycorrhizal fungi, there is a selfish motive involved. They want to be fed during periods of drought, too. So, by placing the water molecules inside plant roots, they assure themselves that the plants have adequate survival to continue to supply them with steady meals of carbon-rich root exudates.

Different plant species produce varying arrays of what are called plant secondary and tertiary nutrient compounds, which are medicinal in nature and promote disease resistance and pest resistance in other plants. They also provide medicinal benefits to animals and humans.

These compounds are transferred from plant to plant via the mycorrhizal highway. Without this occurring, plants are far more susceptible to fungal diseases and to pest insects. In fact, mycorrhizal fungi are the principal immune system for plants against fungal root diseases.

In the past several decades, the use of fungicides by farmers has increased significantly, because typical agricultural practices (like tillage) destroy mycorrhizal fungi populations. In addition, the fungicides used to combat plant fungal diseases are not organism-specific, so they kill not only the target disease-causing organisms, but also the mycorrhizal fungi. This leads to continued disease, and continued use of fungicides, which becomes a vicious cycle.

That is why we practice Regenerative Agriculture at Joyce Farms.

By eliminating tillage, we stop the destruction of the mycorrhizal fungi. By implementing practices such as diverse cover crops instead of perpetual monocultures, and adaptive livestock grazing that stimulates mycorrhizal populations, we not only reduce, but eliminate the need for fungicides. We escape the vicious cycle and turn things back over to Mother Nature.

Soil microbes truly are the foundation of all health, both below the soil surface and above. More than 80% of all plants existing in the world today have developed relationships with fungi. Still others have relationships with bacteria in the soil. If we were to purge the soil of microbes, we would also purge the soil of plants, and purge our world of the ability to produce food.

Implementing agricultural practices that damage or destroy these soil microbes is only doing harm to ourselves and all life around us. Conversely, implementing true regenerative practices that foster, facilitate, encourage, and stimulate these soil microbes provides immense benefits -- our soil is healthy, our crops are healthy, our livestock are healthy, we are healthy, our ecosystems are healthy, and our climate is healthy.

These tiniest of creatures hold the key to solving the primary issues we face today that seem so daunting. If we simply provide for them, they will provide for us. That is why regenerative agriculture and soil health is so important to us at Joyce Farms, and why it should be important to you, too!

July 25, 2019 0 Comments

We are all familiar with erosion and the soil’s ability to wear away, but few people associate soil with growing upward. The truth is, just like we can use poor farming methods to cause erosion of topsoil, we can use regenerative farming methods to literally grow new topsoil!

Regenerative farming depends on an active and balanced carbon cycle, through which plants, soil, and grazing animals create a circle of life that is powered by sunshine. When the carbon cycle is active and balanced, there is a continuous flow of new, carbon-rich organic matter to the soil.

Plants capture energy from the sun and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Next, they use water and minerals from the soil to produce sugars. Some of those sugars are shared with soil microbes in exchange for mineral nutrients. Those root exudates add carbon-rich organic matter to the soil. Grazing animals keep the cycle going (more on that in a minute).

The question is - when all that new, carbon-rich organic matter is added to the soil, where does it go?

Soil is porous. You may naturally assume that any added organic matter would fill the existing pores or holes in the soil, making it more and more solid. If this were true, and you continued to add organic matter, at some point you would essentially be trying to farm on a slab of rock-hard granite.

The good news is, that’s not how it works.

In reality, soil rich in organic matter is more like a sponge than a slab of rock. It's more porous and holds more water. Carbon-rich soil is not rock-hard, but soft under your feet and easier to penetrate with a shovel. That’s because the soil volume has expanded upward, with the help of Mother Nature.

Here's how it happens:

Through regenerative farming practices, animals graze and naturally fertilize an area of land, trampling plants and other organic matter on the surface as they do.

Worms and dung beetles feed on the trampled matter and the manure. They “churn” what’s on the ground and what’s underneath, creating displacement of soil material from below the ground to above it.

Essentially, they excavate the soil from below the ground and put it on top. In the process, new void spaces, or pores, open up in the soil. This new porosity means the soil can hold more water and give access to flowing nutrients.

This is also why you may find a latent seed bank waking up and starting to grow in your soil, long after you thought the topsoil was eroded. This “churning” can carry seeds up near the soil surface, where they can germinate and grow.

The activity of the grazing animals also stimulates the soil microbial population, especially mycorrhizal fungi.

Mycorrhizal fungi produce biotic glues that bind the tiny soil particles together to create much larger particles, opening up significant pore space for water and oxygen infiltration and movement.

So if both organic matter and porosity are being added, and the soil can’t grow down or sideways without compacting, it can only be doing one thing - growing up!

Many experts and even textbooks will tell you that it takes 1000+ years to grow an inch of topsoil, but now we know we can do it much more quickly with regenerative agriculture. Farmers and grazers can add between 0.5% - 1.0% organic matter in a single year.

One of our farmers, Adam Grady, added 3 inches of new topsoil on his farm, in just 2 years!

The photo below was taken on his farm, where our Heritage GOS pigs and some of our Heritage Aberdeen Angus cattle are raised. That line of color separation you see is called the carbon line. The darker soil at the surface is new topsoil that has been grown from increased soil organic matter!

May 10, 2019 0 Comments

We can talk about our products, our heritage animals, and our regenerative practices all day, but nothing makes the impact of customers seeing and tasting for themselves on a farm tour.

Transparency is paramount for us at Joyce Farms, so we’re always happy to take customers out to the farms whenever we can. But last year we began hosting larger 2-day farm tour events that not only show the farms and animals, but really educate about why we do what we do, how we do it, and how our practices impact the bigger picture of human, animal, and environmental well-being.

Last week, we had our first Farm Tour event of the year. The 2-day event began with dinner, drinks, and a short introductory presentation at Ashley Christensen’s Bridge Club in downtown Raleigh.

There’s a reason Ashley was the James Beard Foundation’s pick for Outstanding Chef this year! The custom menu featured many of our Heritage products. It was a delicious way to kick things off!

Bright and early the next morning, we headed to the farms. Our first stop was in Kenansville, NC where we visited farm partner Adam Grady. Our guests were able to learn first-hand about his transition from sustainable to Regenerative Agriculture, and the incredible changes he has seen in only a few years.

We partnered with Adam a little over 2 years ago to begin raising animals for our Heritage Pork program. At that time, he was running a sustainable operation. Adam was willing to transition to Regenerative Agriculture, something we require for all of our Heritage farms, but it was not without a little healthy skepticism. After all, industrial practices are still the mainstream method that his neighbors and most farmers practice; they’re even still taught in agricultural school.

In a calculated leap of faith, Adam agreed to transition 30 acres to regenerative management- enough for us to begin our pork program. He worked closely with Dr. Allen Williams, our Chief Ranching Officer, to put regenerative practices in place.

Here’s what happened in less than one year:

After that first season, he said, “I wish I had just done it all!” The results were so incredible that now, he’s farming 100% of his land (over 1200 acres) regeneratively.

During our visit in Kenansville, our guests saw our livestock, but also examples of regenerative methods.

They saw our rotational grazing methods in action. We showed how we divide larger pastures into temporary smaller paddocks using poly wire, rotating livestock between those paddocks daily, sometimes multiple times a day. In fact, we moved some cattle while we were there, just to show quickly and easily this can be done.

We took a close look at the pastures themselves, as Dr. Allen Williams explained the 5 principles of soil health and how Adam implements each of them:

We talked about forbs (aka “weeds”) and Allen explained how they are actually a GOOD thing. They offer medicinal and anti-parasitic benefits to livestock when they eat just a few bites a day (which saves farmers money). They are also excellent microbe attractors because they are deeply and extensively rooted. Those roots send out root exudates or sugars that attract a wide variety of soil microbes, which are critical for soil health.

Adam showed some of his regenerative farming equipment, including the roller crimper he uses to turn live, grazed cover crop into a bed of organic matter that protects the soil. He uses a no-till planter to plant cash crops into that rolled bed of plant matter, for tremendously efficient growth and yield.

As the trolley ride continued, we talked about heritage breeds and how we are working to bring back some of these now-rare genetics that fell out of favor with the rise of industrial agriculture. First we visited the Gloucestershire Old Spot pigs that we raise for our Heritage Pork.

Then, we saw some of the Aberdeen Angus cattle used for our Heritage Beef.

On our last trolley stop, we saw the always impressive rainfall simulator and slake test demonstrations, to further display how land management practices impact the soil’s ability to absorb and hold water.

Our lunch pig pickin' was outstanding thanks to the folks at Original Grills who cooked a Joyce Farms whole hog for the occasion!

After lunch we hit the road for one of our Heritage Poulet Rouge® Chicken farms in Siler City, NC, managed by our farm partner Larry Lemons. Our guests were able to hear more about the steps we take to raise these birds, including bringing in breeder eggs from France and hatching them in our hatchery. They were also able to see multiple flocks of birds at different stages of growth, and get a first-hand look at the amount of space they have to run around and just be chickens!

We are so thankful to our guests who took the time to come out for a 2-day, information packed Farm Tour! All of us at Joyce Farms are incredibly proud of not only the products we produce, but how we produce them, and we are happy to have the opportunity to share more about that with our customers.

See more photos from the tour on our Facebook page!

April 19, 2019 0 Comments

Each year, Earth Day brings millions of people together to take action against threats to our planet, like climate change, desertification, and endangerment of native animal and plant species.

There are plenty of ways we all can give back to the planet: clean up trash, plant a tree, or volunteer for a conservationist effort, just to name a few.

As chefs and restauranteurs, you have another powerful opportunity to give back to the planet every day by using products from regenerative farms on your menu.

By serving products raised using regenerative agriculture (also known as carbon farming), you support a way of farming that fights threats to our planet and contributes to its rehabilitation from decades of industrial farming practices.

When you serve products grown regeneratively, you give back to the Earth by:

Regenerative agriculture can stop and even reverse climate change, which is the result of excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Farming regeneratively builds soil health, and when soil is healthy and full of microbial life, it is able to draw down excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere where it can be used to grow plant life.

Think of how often you hear about reducing carbon emissions to stop climate change - probably every day. But reducing emissions does nothing for what is already there.

The fact is, even if we all stopped driving cars tomorrow, it would do nothing to fix the excess carbon dioxide already in our atmosphere. We need to put that carbon back into the soil, where it can be used. Regenerative agriculture does that and more.

This video from Kiss the Ground gives a quick primer on how the soil can help reverse climate change:

To produce healthy food for generations to come, we need healthy soil. Sadly, degenerative practices like tilling, chemical use, and overgrazing have left most of our soil degraded and barren.

Regenerative farms do not use chemicals or tilling, and use a variety of year-round cover crops to protect the soil from extreme temperatures.

Livestock graze, while naturally fertilizing the land and trampling organic matter into the soil.

Using adaptive grazing methods, the animals are moved to new areas of pasture regularly, allowing plant life to recover and preventing the effects of overgrazing. With a variety of plants, soil life and fertility thrive.

Regenerative farming requires integration of livestock, but that is only successful with animal breeds that fare well in pasture-centered conditions. Old-world heritage breeds are perfect for the pastured life, because they have hearty immune systems (eliminating the need for antibiotics) and flourish on what has always been their natural diet.

Before the rise of industrial agriculture, these historic breeds were preferred for meat production. Unfortunately, most fell out of favor as high yields became the priority in agriculture. Animals were selectively bred to grow bigger and faster in the name of efficiency and price. As a result, many heritage breeds are now threatened or endangered.

When you use heritage breed products, you help protect these breeds and our planet's biodiversity. For example, our Heritage Old Spot pigs are on the Livestock Conservancy’s list of endangered breeds. As we grow our Heritage Pork program, we continue to breed and grow our herd. In doing so, we are helping to preserve these historic genetics for future generations.

Since regenerative farming does not involve chemicals or pesticides, it does not add harmful toxins to the soil, which also prevents those toxins from running off and contaminating our rivers, streams, and other waterways. As the soil draws in carbon and becomes healthier, overall runoff is reduced because the soil is able to absorb water much more efficiently.

By choosing products from regenerative farms for your menu, like the meat, poultry and game products from Joyce Farms, you can take pride in serving memorable meals that are not only more flavorful and nutritious, but that help save the planet. Now that’s something worth bragging about in your menu notes!

February 18, 2019 0 Comments

The message is spreading about regenerative agriculture, and more and more farmers, consumers, and medical professionals are realizing the importance of making a big change, now.

One project taking big strides to promote the regenerative message is called Farmer's Footprint and is led by Seraphic Group and Dr. Zach Bush M.D. It's a powerful documentary series that shows how critical regenerative agriculture practices are in reviving the health of our environment and fighting chronic disease in humans. Their mission is to regenerate 5 million acres by 2025.

The first short documentary of the series was released last week and features our own Dr. Allen Williams. It shares the story of a small family farm in Minnesota transitioning from conventional farming to regenerative agriculture. It also presents eye-opening scientific findings from Dr. Zach Bush about the connection between destructive, chemically dependent farming practices and chronic disease.

Please take the time to watch and share this incredibly powerful film, and learn more about the project at farmersfootprint.us

Farmer's Footprint | Regeneration : The Beginning from Farmer's Footprint on Vimeo.

February 14, 2019 0 Comments

The love story between livestock and our land began a long time ago as large herds of grazing ruminants like bison roamed from coast to coast. Their natural behaviors helped shape the land as we know it.

As Dr. Allen Williams has explained, “from an ecological perspective, grazing and browsing ruminants have been an incredibly important part of every grassland, prairie, savanna, and woodland system. These ecosystems evolved under the influence of these grazing and browsing ruminants.”

After Mother Nature set them up, the animals and land flourished together, with a true give and take relationship. In the spirit of Valentine’s Day, let’s take a closer look at why these two are so good together:

The land feeds the livestock with plant life

Grazing spurs plant regrowth and increased soil life

Historically, bison traveled across our nation in herds and would graze an area, then move on to another, never overgrazing any one spot. As the herds moved, the partially grazed plant life left behind would begin trying to regrow as quickly as possible.

To do that, the plants draw in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and use it to make sugars. They use some, and exchange some with soil microbes in exchange for important nutrients also needed for growth.

So basically, while the animals are enjoying a nutritious meal from the land, they’re also giving back by strengthening the soil. Each time they return and regraze (after complete regrowth), the process repeats, creating more and more microbial life in the soil and a variety of plant life above ground.

The land feeds the livestock with plant life

Livestock give the soil a protective cover

As livestock graze the land, they are also trampling the ground, creating a flattened cover of plants and grasses that protects and insulates the soil. As the trampled "mulch" of plants decomposes, more organic matter (carbon) is added to the ground. This helps build fertile and biologically active topsoil that is critical for ongoing productive and profitable farming.

The ground cover also creates a perfect environment for micro life, like bacteria, fungi, earthworms and dung beetles (all of which are important for forming new soil).

The land feeds the livestock with plant life

The livestock naturally fertilize the land

As livestock graze, they digest grasses and naturally fertilize the land, giving plant life access to all the nutrients needed to grow. Healthy soil can make use of this above-the-ground fertilization very effectively, but if the soil is already degraded, with no life and no dung beetles, it's unable to carry out this natural process.

As you can see, the relationship between livestock and land is strong - they need each other. Aside from providing meat, livestock plays a number of critical functions on a farm. Unfortunately, in recent years, industrialized farming drove quite a wedge between them. Farmers looked to machines and chemicals to do what livestock took care of naturally, which is expensive for the farmer, leads to dependence on chemical inputs, and produces food that lacks flavor and nutrients.

The fact is, livestock and farms belong together. In today’s world, we no longer have the natural, large roaming herds of bison that can carry out these functions. But by managing our farmland using regenerative practices, including adaptive multi-paddock grazing, we have a chance to put livestock and land back together, forever!

The Secret Is Out! Cows Are Not The Problem... It's How They're Raised.

Allen Williams on Replacing Monoculture Farms with Adaptive Grazing

Dr. Allen Williams Participates In New Study Of Adaptive Multi-Paddock Grazing

Adaptive Grazing: So Old It's New

November 15, 2018 0 Comments

As we enter the week of Thanksgiving, one thing we are extremely thankful for at Joyce Farms is the growing community of chefs, food and agriculture industry professionals, and consumers who are increasingly eager to learn about our mission and practices and how they promote animal welfare, regeneration of soil and ecosystems, and more flavorful and nutritious food.

Last month, we brought some of that growing community together for a series of four farm tour events. We welcomed chefs and culinary professionals from all around the country, and we were thrilled to find that they were just as eager to learn about what we do as we were to show them!

Our goal was to provide an educational experience on the importance of genetics, animal welfare, and regenerative farming as it relates to the flavor and quality of meat and poultry, and the effect different farming methods have on our environment.

Here's how it went...

Part 1: Bridge Club Dinners

Each farm tour was preceded with a dinner event the evening before, at Chef Ashley Christensen's Bridge Club in Raleigh.

The Bridge Club loft was a perfect backdrop for getting to know our guests better and enjoying a truly memorable meal of Joyce Farms products, expertly prepared by Chef Ashley and her team.

Each evening began with a few drinks, great conversation, plenty of delicious appetizers featuring Joyce Farms Heritage Poulet Rouge™ chicken and Heritage Bison!

Appetizers included picnic-style Poulet Rouge™ chicken with hot honey, Poulet Rouge™ chicken liver mousse, bison tenderloin tartare, deviled egg topped fried green tomatoes, and Poole's pimento cheese with saltines.

Next, we shared a mouthwatering family-style feast that featured our Heritage Beef and Heritage Pork. Main dishes were Chateaubriand of beef tenderloin and braised pork shanks with ramp chimichurri.

And while it doesn't look like it so far, we did more than eat and drink during our Bridge Club events! Before the meal, our guest saw a special screening of A Regenerative Secret, a recently released mini-documentary project that Joyce Farms sponsored and that features our Chief Ranching Officer Dr. Allen Williams along with Finian Makepeace of Kiss the Ground.

After each evening's dinner, we talked more with the groups about our mission and products, our unique heritage breeds, and our regenerative agriculture practices. We told our guests about the things they would see an experience on the farms the following day, including the recent damage from Hurricane Florence, which hit only two weeks before our first tour.

We prepared our guests to see real, working farms - not "show farms" like some producers use to put their best foot forward (and to hide their worst). We believe in full transparency, and in showing our customers the real story, including successes and challenges. Mother Nature can be unfair, and as farmers and producers, we have to learn to deal with, and recover from, those times. It was unfortunate that the pork farm was heavily flooded with rainfall from Hurricane Florence, and a lot of our pastures were damaged. Rather than canceling our tours, we chose to view the storm damage as a great opportunity to share more information about our regenerative farming practices and how they are helping the farm to recover more quickly.

Part 2: Days On The Farm

Our farm days were full ones with plenty to see and learn. We covered topics like animal genetics, soil biology, and regenerative agriculture, to name a few.

Each farm day started with a visit to Dark Branch Farms, owned and operated by our farm partner Adam Grady. Adam and his family primarily raise the Gloucestershire Old Spot pigs for our Heritage Pork, but the farm is also home to some of our Aberdeen Angus cattle. Our tour guests learned about the history and characteristics of these two old-world breeds, and how we are helping to revive heritage breeds like the Old Spot from endangerment or extinction.

Next, Allen Williams gave a powerful in-field lesson about regenerative agriculture practices and their potential to transform not just the food industry, but our environment overall. He spoke about desertification and the unhealthy state of most of the world's soil. He stressed the importance of healthy soil as a fertile growing environment for flavorful, nutrient-dense food for livestock and for us. With help from Adam Grady, he used real examples from the Heritage Pork farm to cover key regenerative principles like no tilling or chemical use, planting cover crops, and integrating livestock with planned grazing techniques to restore the health of the soil.

The regenerative lesson continued with a Rainfall Simulator demonstration led by a representative from the USDA's Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Our guests saw how different kinds of land and grazing management affect soil health. For this powerful demonstration, samples of soil are used from different pastures that have been managed in different ways - some with degenerative practices like tilling or chemical use, others were managed using regenerative practices like livestock integration and rotational grazing without tilling or use of chemicals. These samples are placed in trays side to side under an overhead sprinkler, with clear buckets underneath.

When the demonstration begins, the overhead sprinkler simulates a rainstorm. When the water hits the soil, the samples that have been subjected to degenerative management produce much more runoff into the buckets below, indicating the soil is unhealthy and has poor water infiltration. This runoff causes erosion and carries away nutrients and sediment with it. The samples from pastures with regenerative methods in place are able to take in more water, which decreases runoff.

After the rainfall simulator, our guests had plenty of time to "digest" what they learned and ask questions while enjoying a Pig Pickin' on the farm! For all of our farm tour lunches, we teamed up with Original Grills in Raleigh, and they did an outstanding job cooking up one of our Old Spot hogs with all the fixins.

After lunch, we headed to the small farm where our Heritage Black Turkeys and some of our Heritage Poulet Rouge™ chickens are raised by farmer Larry Lemons.

Coming to the farms, seeing our practices, meeting the farmers, and hearing our story first hand is the very best way to get to know our company and understand the care that goes into our products. Thank you to all of our farm tour guests - it was truly an honor to host such passionate and talented groups chefs and culinary professionals!

Another big thank you to the following groups and individuals who helped make our fall farm tours a success!